Ryan Derenberger is a freelance journalist and editor, a Journalism and AP Language teacher at Whitman HS in Bethesda, MD, and the founder of 'The Idea Sift.' He also serves on the board of directors for student journalism nonprofit 'Kidizenship.'

October 27th, 2021 at 7:30 pm EDT

“He could never do that live. That’s not real music.”

Dehydration to innovation, “gatekeeping” — an artificial defining of what “is” and what “isn’t” — stands opposite to art. Well into the third decade of the new millennium, gatekeepin’s form within music fandom is as loud and pretentious as ever.

But sworn purists mourning the supposed loss of talent in the contining basement-producer era will look petty and hypocritical even with common examples in frame. Let’s flip the guitar, Hendrix-style, and use some of our best and even most popular musicians to demolish our worst armchair takelords.

Golden age rock guitarist, vocalist, and producer Jeff Lynne (ELO, Traveling Wilburys) was back in the 70s among the first rock musicians to produce his music and others’ through a level of near-absurd “tracking,” the studio magic of repeated and layered takes. Layering is how Lynne was able to give us such brand new, lush sounds, like the chorus in ELO’s biggest hit on the Billboard charts, “Don’t Bring Me Down.”

He later produced some of Tom Petty’s most massive and enduring songs (“I Won’t Back Down“, “Free Fallin’“), while Petty’s band the Heartbreakers came to hate the tedious Lynne and his process. Lynne once had Heartbreakers keyboardist Benmont Tench hit a single key for a whole track, Tench explains in the ’07 Petty documentary Runnin’ Down a Dream. Drummer Stan Lynch actually quit those first Petty/Lynne sessions, he said, drawing a line in the sand about “Free Fallin'”, of all tracks, being a poorly written and limp, studio song.

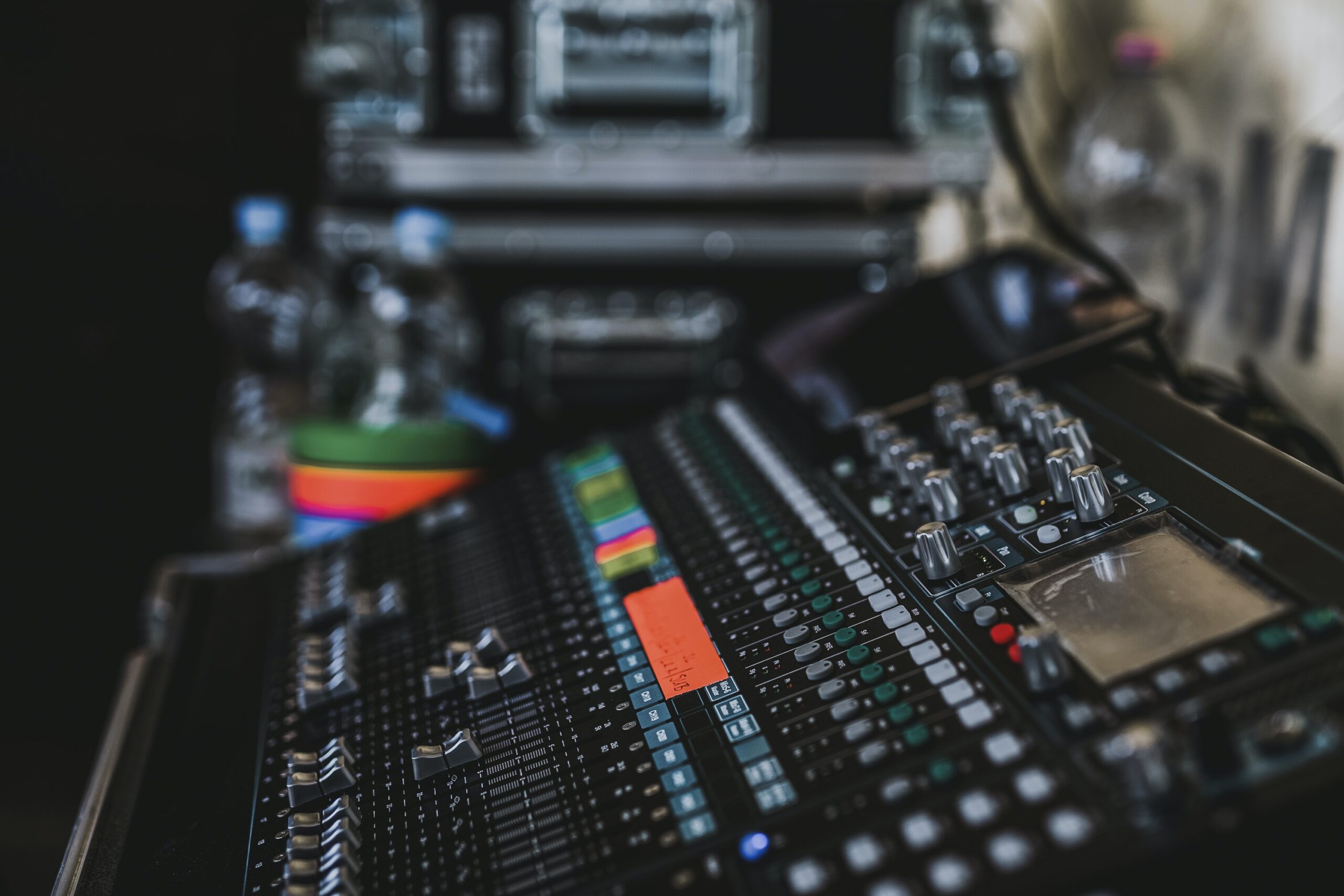

So why bother recording like Lynne? Why bother with maniacal precision? With everything tracked separately, and often multiple times, a musician affords themselves uninhibited creativity as a composer behind the boards. Lynne felt that. There is no sound the brain seeks that fingers can’t then conjure. Musicians can double-track anything to fill frequencies, not just guitar or vocals, pan anything for any time, automate any effect, anywhere.

Garbage drummer Butch Vig, go-to producer for the Pixies and other grungers, recalls actually lying to Kurt Cobain during the Nirvana Nevermind sessions over which Vig served as producer. Counteracting Cobain’s common anti-studio bias, Butch told Cobain early “Drain You” guitar takes weren’t any good, to “do it again” — just so Vig could keep tracking Cobain without him knowing.

In “Drain You”, Vig got five different, simultaneous rhythm guitar tracks out of Kurt, with different distortion pedals, to create one, new and blended sound — all from a band with a single guitarist. He showed the world what it’d sound like if five of Kurt were able to play at once and fill our sound spectrum with talent.

The volume, equalizer, and effect knobs Vig could vary in post as he pleased, never needing a return to the sound booth, and in the thousands upon thousands of subtle combinations between and among those sound waves, Vig found Nirvana’s Nevermind sound, an absolute monolith of a branch in music history, and one Vig is arguably more responsible for than Cobain himself.

Predictably, and a tad pretentious, Cobain later mourned the wall-shattering polish, valorizing thinner sound waves, tinny demos, and anything else categorized as non-commercial.

Vig, meanwhile, continued to create new sounds. On Garbage’s single “Stupid Girl“, he double-tracked himself playing drums. Without the editing and splicing available on modern digital audio workstations, his was a rare feat for the time, requiring the chops of a metronome for the two drum takes to sync well. He recycled the riffy beat from The Clash’s “Train In Vain” to make a veritable melody out of percussion, and resurrect a piece of music that still had life to it. The tracking method is what made the song work, while shoegaze guitars jangled as texture.

You cannot recreate the beat live unless you stage two drummers with full sets, or rely on a digital audio workstation to mimic the same.

The Smashing Pumpkins, too, are renowned for adding a ton of guitar tracks in the studio. “Thick” is their signature sound, and it’s tied to grunge and post-grunge rock alike, distinguishing and statement-making after a time of high-treble L.A. metal. On stage, the Pumpkins mimic the full effect now with three guitars and careful FX chains and amp modeling. Studio-positive, frontman Billy Corgan embraced the need to manipulate every aspect of the sound from his brain, to the tape, independent of live shows (which, incidentally, he also obsesses over). Corgan still uses every tool available to him, he says, mulling over guitar pick-ups, pre-amps, pedals, and yes, tracking.

There’s no traditionalist telling him, “Well, that’s not how we used to do it in Nashville.”

The all-too-common gatekeeping refrain that the studio process is inferior or impure is an argument in disguise about what it really means to create content. But studio composition demands a different kind of creativity than live music. A street artist’s facility with pastel is a different art, even, than is the months-long muralist’s. The tradition of acknowledging the chasm between “live” and “lived-with” has not merely been accepted or secretly leveraged; it’s been ebulliently embraced by some musicians, too.

Open, guitar icon Jimi Hendrix exploited and explored the dichotomy with his second and third albums Axis: Bold As Love and Electric Ladyland. Hendrix wasn’t composing psychedelic sound loops in the studio only in ways he could reproduce on stage. Brian Wilson embraced the veritable new art, too, when he wrote the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds with irreproducible dubs — yet cemented his album’s place in rock history, that supposed purist of pure genres.

Despite the precedents in rock, though, it’s hip hop where the obvious legitimacy of producer-as-composer should have calcified for good. For how long have hip hop musicians had to hear that rap wasn’t “real music,” or that a drum machine isn’t a “real instrument”? Every track, every note, every sample, they knew, they could manipulate with complete precision, and they could vary those choices within each note. Every single hit of the hi-hat could have a different velocity, a different attack vector as a soundwave, even. The ride cymbals on “Peter Piper” are perfect and iconic. John Bonham doesn’t need to be able to play the sequence live for the Run DMC song to do the one thing that all great art does: “move.”

Wagner and Tchaikovsky, too, wrote parts that were impossible to play, but given their monolithic cultural currency, you’d never know it.

Music gatekeepers, ignoring not only sound-art movements in dozens of sub-genres but some of your own established greats, too, you’re attempting to deprive the world of variation in music and falling victim to what logisticians call a “genetic fallacy,” discriminating worth on origin alone. The medium of sound is a transcendent one that allows artists to vessel messages and couch wisdom. Please, never beach an artist. Enjoy their waves, however they’re made.

Anything that comes out of a studio that isn’t live and reproducible by the musician is definitionally inferior, the work of lazy and lucky modern musicians passing off craft as art, and knob-turning as talent.

THE SIFT

The art of sound may or may not involve live, reproducible products. In either instance, and to every degree between, most valuable is an artist’s ability to create the work they envision to its purest extent, such that an audience engages the experience in transformative ways.

Ryan Derenberger is a freelance journalist and editor, a Journalism and AP Language teacher at Whitman HS in Bethesda, MD, and the founder of 'The Idea Sift.' He also serves on the board of directors for student journalism nonprofit 'Kidizenship.'