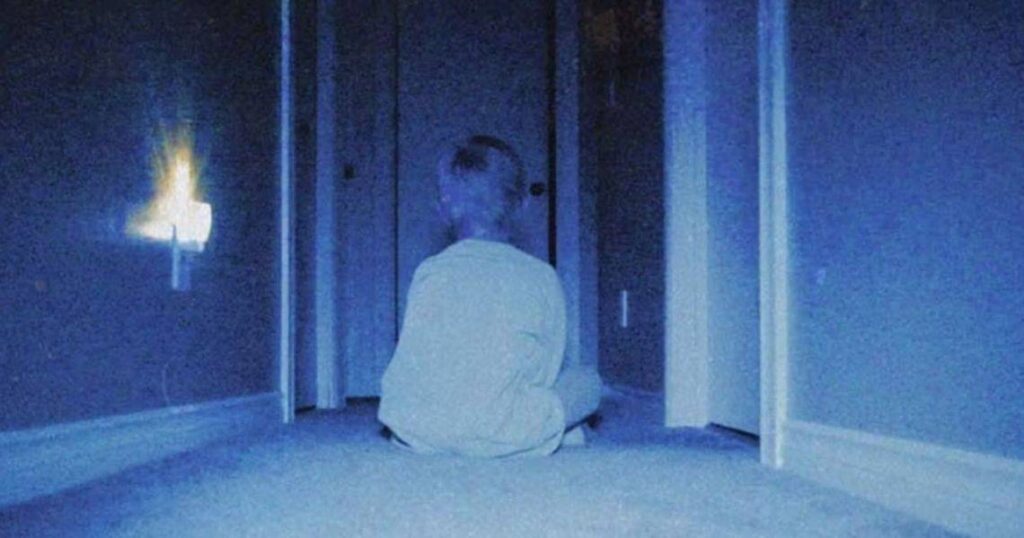

Skinamarink plays like the opening credits of a David Fincher movie spread over 90 minutes. It’s a series of odd angles and silhouettes, an occasional flash, an even less occasional word, all run through the most contrived Instagram filters.

The story follows — literally, only from behind — two children who wake up to an empty house, theirs, but absent windows and doors. The rest of the story adds about two sentences. I’m not sure Skinamarink is even a movie; it’s a technical demo, a plodding slideshow of unlevel ceiling corners to trigger home inspectors.

The most effective parts of it are the least frequent, the turning of a corner only to finally find a human sat and stiff, or a face bleeding through the ominous animations we project onto pitch black. Instead of more, we meditate on a two-minute shot of Duplos. What’s indelible are several shots so thick with artificial VHS effects that the pixels of an apparition seem to float and the black under a bed, chug.

Skinamarink never had a chance theatrically. I saw it at an AMC, in a new chair more comfortable than any I own. I was a tough sell for unease. The theater was packed, but entirely respectful and there for a genuine horror experience — the kind that scares you so much, a part of you categorizes it as self-abuse — but yawns and seat-shifting soon became common. Twizzlers and Coke aren’t exactly depressants.

Early screenings and viewings benefitted from buzz, zipping among the bowels of the internet. If the film were bootlegged and viewed on a laptop under the covers, as for many it was, I can imagine all that glorious, elated regret that may come with it. But this is not a movie, the type of art that tells a story and changes you through the power of motion. There’s almost no such thing as motion in this world.

Perhaps the most damning feature of the demo we’re given, one that in consideration, renders me with considerably less guilt when bucking Skinamarink‘s cult masterpiece status, is how unbelievably unearned and arbitrary the few jump scares are. They are abrupt volume cranks, paired with a mildly creepy image each and placed just far enough apart to keep suspense, however blunted, alive. They’re little more than the prank you played on friends with a YouTube video in 2006: “At the 24th second, a skull cuts in and screams!” If I didn’t know how earnest the director actually was, I’d assume this entire endeavor to be something of the same, a social experiment we’re all the subjects of, to see how far the power of suggesting a masterwork actually creates one.

The catch-all excuse that Skinamarink is just realistically dreamlike rings more hollow than the movie, even though the director reportedly solicited actual nightmares from others as inspiration for a film. Nightmares don’t have slide a/b shifts with concrete objects disappearing in a frame, the same effect of crossing your arms and nodding your head in an “I Dream of Genie” episode. Nightmares are fluid, twisted, dynamic, and thrashing, even when deliberate and slowed.

Be glad Skinamarink exists. Be thankful for experimental films. But let’s not coronate this one as some kind of postmodernist context killer and ultimate terrifier. This is effectively, and purposefully, nothing, a mess of a plating the chef dares to serve anyway as a “deconstructed” dish.

There will be a class of career trolls who lambast naysayers with a hundred versions of “You’re just not refined enough to get it.” Have those people over for dinner, and dump raw spaghetti and sauce on their laps. When they gawk, tell them, “It’s supposed to elicit a reaction.”

Ryan Derenberger is a freelance journalist and editor, a Journalism and AP Language teacher at Whitman HS in Bethesda, MD, and the founder of 'The Idea Sift.'